The Beatitudes

Carl Heinrich Bloch. The Sermon on the Mount (oil on copper), 1877.

The Museum of National History, Frederiksborg Castle, Denmark.

[Notice the inclusive group of people listening to Jesus: men, women and children, some attentive, some skeptical, but all focused on him. The bearded man behind Jesus may be a self-portrait of Bloch. Notice, too, the whimsical little girl on the left, picking a butterfly off the head of a man at prayer.]

(Listen to an audio version of the blog post below!)

Jesus was a master teacher, and his “Sermon on the Mount” in Matthew 5-7 is one of his most memorable teachings. The “Sermon on the Mount” is a perfect example of expository teaching, and it consists of four perfectly balanced sections: 1) the “Beatitudes,” a clever and memorable introduction (5: 2-16); 2) six propositions that exceed the law (5: 17-48); 3) six concrete actions to implement the law (6: 1 – 7: 6); and 4) a dramatic “call to action” (7: 7-29). I’d like to devote this blog to the “Beatitudes,” the opening section of the “Sermon on the Mount.”

We should note several things about this clever and memorable introduction. First, it consists of nine statements, the first eight being the beatitudes proper and the ninth being a summary statement. Each of the nine statements begins with the same word, μακάριοϛ [mak-ar’-ee-os, “blessed”]; the Hebrew would be אֶשֶׁר, [eh’-sher, as in Psalm 1, “blessed, indeed, is the man . . .”]; the Aramaic (Jesus’ native language) would be בריך [ber-ak’]; and the Latin would be beatus, from which we get the term, “beatitudes.” Starting each of the eight beatitudes with the same word is a rhetorical device called anaphora, and each statement employs parallelism: “Blessed is A, for they shall be B; blessed is C for they shall be D,” and so on. Add sound repetition to that and you get very memorable statements.

And notice, too, that each of the eight statements is counter-intuitive:

“Blessed are the poor in spirit,

for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.”

Jesus’ listeners would surely have thought:

“Blessed are the rich in spirit,

for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.”

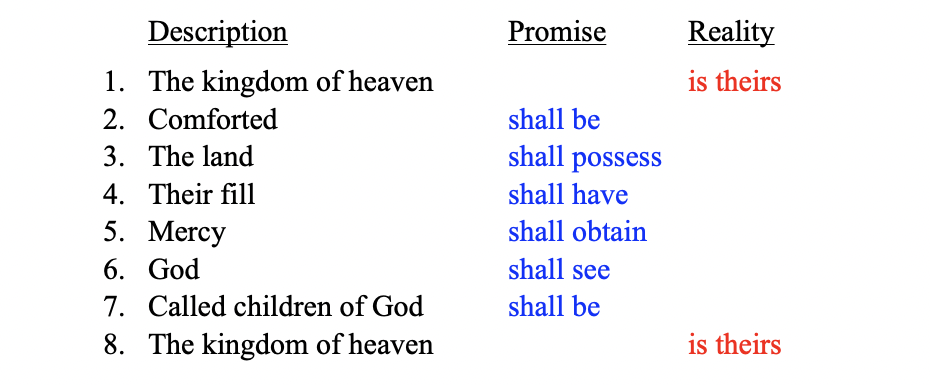

Now, look carefully at the verb tenses Jesus uses:

Beatitudes 1 & 8 are present realities, whereas, beatitudes 2-7 are promised future realities. On one level the beatitudes speak of a down-trodden people who may be poor in spirit and persecuted, but who nevertheless have God with them, and their true home is the kingdom of heaven, a present reality. Life may be difficult now, but in the future they will be comforted, the land will be theirs, they will be satisfied, shown mercy, see God and be called children of God. That’s certainly one way to understand the beatitudes, viewing them not as a moral or social code of ethics, but as a statement of current reality, of God’s people living under the yoke of both Roman occupation and religious oppression and of one day that dual-yoke being lifted from them. Such an understanding, of course, is not limited solely to 1st-century Palestine, but to any time and any people living under political and religious oppression. But the 9th beatitude, the capstone to Jesus’ clever and memorable introduction, suggests a more personal, more spiritual reading:

“Blessed are you when they insult you and persecute you and falsely utter every kind of evil against you because of me. Rejoice and be glad, for your reward will be great in heaven. Thus they persecuted the prophets who were before you.”

Jesus never said a word about the Roman occupation. Rather, he aimed his fiercest criticisms at his own people and at their religious leaders . . . exactly as the prophets of old did: Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel and the rest. Jesus never got down into the muck and the mire of worldly politics, instead speaking of the kingdom of God, both within and without. So, let’s probe deeper into the beatitudes and seek to find a more personal understanding of them, working through them one by one, noticing that they are sequential:

“When [Jesus] saw the crowds, he went up the mountain, and after he had sat down, his disciples came to him. He began to teach them, saying:

‘Blessed are the poor in spirit,

for theirs is the kingdom of heaven . . .

As we noted earlier, Jesus’ statement is entirely counter-intuitive, meant to catch his audience’s attention. Notice that it’s not “blessed are the poor” (as in Luke 6: 20), but “blessed are the poor in spirit” [πνεῦμα, nyoo’-mah], in the sense of one’s inner-most being, one’s spirit or soul. I should point out from personal experience, that there’s nothing blessed about being poor: I’ve been poor and I’ve been not; not is considerably better! We read in Proverbs 20: 8-9:

“Give me neither poverty nor riches,

but give me only my daily bread.

Otherwise, I may have too much and disown you

and say, ‘Who is the Lord?’

Or I may become poor and steal,

and so dishonor the name of my God.”

The first step toward God is recognizing one’s own interior poverty, the dreadful emptiness in one’s own heart that only God can fill. Indeed, you can’t take a single step toward a Savior until you recognize your need to be saved.

Blessed are they who mourn,

for they will be comforted . . .

Those who mourn [πενθέω, pen-theh’-o] includes bereavement, of course, but it goes far deeper than that. Recognizing one’s own interior poverty is one thing; mourning over it is quite another. One can recognize that interior poverty and accept it as an unavoidable existential reality, try to fill it with distractions, possessions and entertainment, or face it head-on, staring into the abyss and mourning over the utter emptiness in one’s own heart.

Blessed are the meek,

for they will inherit the land . . .

The “meek” [πραΰς, prah-owce’] should not conjure up the 1924 comic strip character, Casper Milquetoast, one who speaks softly and gets hit with a big stick! No. We read in Numbers 12: 3 that “Moses was very meek [עָנָו, aw-nawv’], above all the men which were upon the face of the earth” (KJV). Yet it was Moses who confronted Pharaoh, the most powerful man of the ancient world, and demanded on behalf of God: “Let my people go” (Exodus 5: 1)! And when the Israelites worshipped the golden calf, it was Moses who rallied the Levites, and went through the camp killing 3,000 apostate Israelites (Exodus 32: 28). That’s no Casper Milquetoast! The “meek” [πραΰς, prah-owce’] in this instance are those who recognize the vast emptiness in their own heart, mourn over it and recognize that the proper posture before God is flat on one’s face in utter humility and submission before God almighty, creator of the universe, the one who created us, who breathed into us the breath of life, and against whom we have sinned.

Blessed are they who hunger and thirst for righteousness,

for they will be satisfied . . .

Once recognizing our interior emptiness, mourning over it and taking a proper position before God, we then desire desperately to be in a right relationship with God, to hunger and thirst for righteousness [ δικαιοσύη, dik-ah-yos-oo’-nay], to be viewed by God as acceptable and pleasing in his sight.

Blessed are the merciful,

for they will be shown mercy . . .

Once viewed by God as acceptable and pleasing in his sight, we then have an obligation to be merciful [ἐλεήμονες, el-eh-ay’-mone] to others who are in the same position as we were, others who may not yet recognize the root cause of their emptiness, much less have a longing for God. They may well mock God and hold you in contempt as a pitiful, ignorant fool, dreaming of “pie in the sky, when you die.” Our attitude should not be one of contempt or hostility toward them, but one of mercy . . . for they are where we once were. We know how they feel.

Blessed are the clean of heart,

for they will see God . . .

“Blessed are the clean of heart,” or better, the pure [καθαροί, kath-ar-oi’] of heart. On one level it pictures a vine pruned clean in order to bear abundant fruit. We all need to have extraneous junk removed from our lives, the objects and thoughts we’ve accumulated in an attempt to fill our emptiness. Sometimes we have to “clean house” to make room for God. On another level it speaks of motive. Why do we want an intimate relationship with God? Do we desire it for what we will get in return? If so, are we nothing more than spiritual mercenaries? Or do we love God for who he is, not for what we get? That’s a question we all need to ponder. And it’s a complicated question that we must probe carefully or we’re apt to settle for a superficial answer. C.S. Lewis addressed this very question in a sermon that he preached in the Church of St. Mary the Virgin at Oxford on June 8, 1941. It was published a few months later as “The Weight of Glory” in the journal Theology 43 (1941), pp. 263-274, and it has been reprinted and anthologized many times since. In his sermon Lewis draws an analogy between a schoolboy learning Greek and the Christian life. In the beginning, learning Greek is a difficult task with few rewards, save for decent marks on weekly exams or praise from parents or teachers. The Greek-learning schoolboy who struggles with the drudgery of grammar, syntax and rhetoric could never imagine the sublime satisfaction of reading for sheer enjoyment the Gospels in their original Greek, Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey or the tragedies of Sophocles. In relation to heaven, the Christian is in much the same position as the schoolboy. Those who have attained eternal life and enjoy the beatific vision of God, experience it not as a reward for their earthly efforts, but as the very consummation and completion of their earthly existence. As with the schoolboy, says Lewis, “poetry replaces grammar, gospel replaces law [and] longing transforms obedience, as gradually as the tide lifts a grounded ship.”

Blessed are the peacemakers,

for they will be called children of God.

“Blessed are the peacemakers” [εἰρηνοιός, i-ray-nop-oy-os’]. The word “peacemakers” in no way implies pacifism; rather, it refers to those who actively bring conflict to an end. It is the core principle of St. Augustine’s position in favor of a “just war,” a war that brings about a greater peace. On a more personal level, “blessed are the peacemakers” follows the sequential movement of the beatitudes themselves. A person who recognizes his own interior poverty, who desperately longs to be right with God, who positions himself in a proper relationship with God and who does so for the right reasons will strive to bring inner peace to his own life and to the lives of those around him.

Blessed are they who are persecuted for the sake of righteousness,

for theirs is the kingdom of heaven . . .

The last of the eight beatitudes naturally follows the previous seven. A person who embodies the beatitudes will invariably be persecuted [διώκω, dee-o’-ko, a prolonged and causative form of the primary verb, dio, to “flee” or “pursue”]. The values of this world stand in stark contrast to the values expressed by Jesus in the beatitudes. To understand this, we need only consider Jesus’ fate at the hands of the Jewish religious leaders, the crowds on Passover pilgrimage to Jerusalem and the Roman authorities themselves. For many, Jesus evoked scorn, fear and fierce hatred.

Blessed are you when they insult you and persecute you and falsely utter every kind of evil against you because of me. Rejoice and be glad, for your reward [is] great in heaven. Thus they persecuted the prophets who were before you.’”

Verses 11 & 12 offer a concluding statement to the eight beatitudes. If one truly embodies the “beatitudes” the world will “insult you,” “persecute you” and “falsely utter all kinds of evil against you.” That can happen if one follows any controversial path. But Jesus adds a qualifier: “because of me.” And that qualifier makes all the difference. And if that’s the case, then you may indeed “rejoice and be glad for your reward [is] great in heaven.” The grammar here is a little tricky. Our NAB translation places the “reward” [μιδθός, mis-thaws’, a nominative singular] in the future by following it with “will be”; whereas, a literal translation of ὁ μιδθός ὑμῶν πολύς should read “the reward of you is great” [or “your reward is great”], a present tense rendering. That’s an important difference, for as we noted above, the 1st and 8th beatitudes reflect one’s present position in the kingdom of heaven, whereas the 2nd through 7th beatitudes reflect a future promise.

Although we may be insulted, persecuted and slandered because of Christ, we experience such contempt as current residents in the kingdom of heaven, a kingdom that is our true home. We don’t live in this world; we are simply pilgrims passing through it, pilgrims charged with being ambassadors of Christ. So, even though we may suffer insult, persecution and slander on our pilgrimage, we are honored all the while by our fellow citizens who are “at home.”

Built between 1936 and 1938, the modern Church of the Beatitudes in Galilee sits atop the remains of a 4th-century Byzantine church on the traditional site of Jesus’ teaching, just a 20-30 minute walk from Capernaum, a place Jesus often went to teach. The floor plan of the church is octagonal, one side for each of the eight Beatitudes, with the dome representing the concluding statement.

View of the Sea of Galilee from atop the Mount of Beatitudes.

Photography by Ana Maria Vargas